When Worry Becomes a Way of Life

03 February 2026

Recognising the Quiet Toll on Your Body and Mind

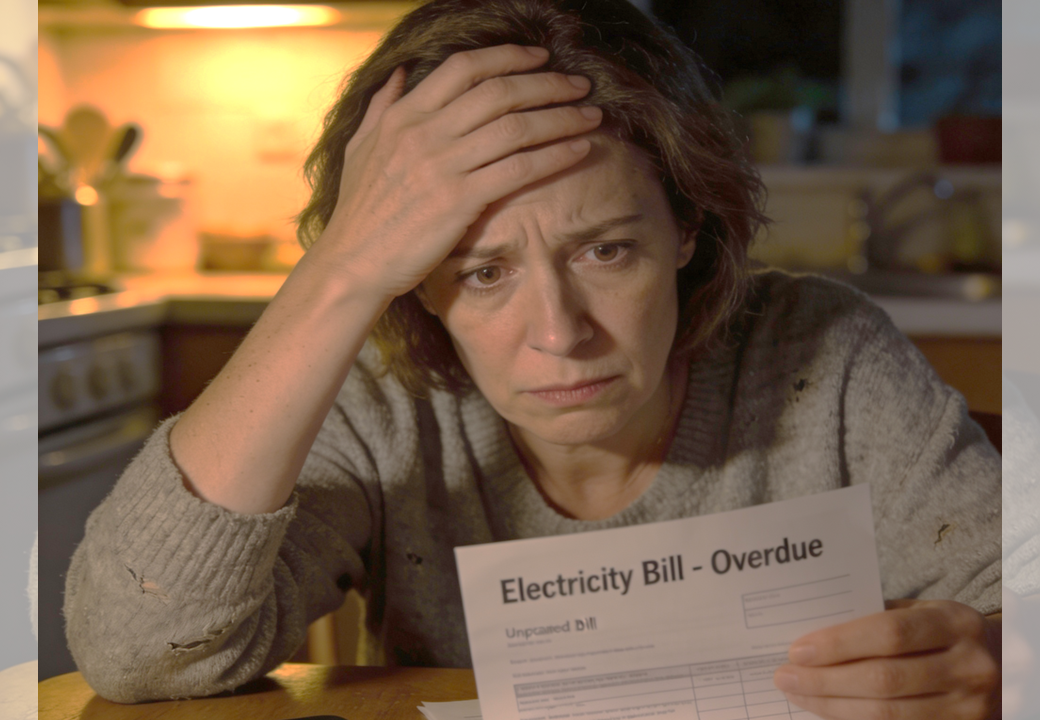

Worry often shows up appearing perfectly reasonable: a late bill, a health check-up, a child who doesn’t text back. Over time, though, worry can quietly shift from an occasional visitor into a way of life, and when it does, it doesn’t just fray your mood — it affects your entire system.

Worry as a Stress Signal, not a Personal Failure

Worry is, at its core, a stress response to uncertainty. When your mind cannot predict what is coming, your body prepares for danger: stress hormones rise, your heart rate changes, and your nervous system moves into high alert. This is not a sign that you are “too sensitive” or “broken;” it is a sign that your system is trying to protect you.

The trouble begins when this alert state becomes chronic. A little stress can help you move quickly in a crisis. But when worry sits with you day after day, your body starts paying a price: blood sugar is affected, digestion becomes unsettled, mood dips, and your immune system can weaken over time. You may notice yourself feeling more depleted than “just tired,” as if your reserves are draining faster than you can refill them.

How Worry Shows Up in the Body

For many people, the first signs that worry is taking up too much space appear physically. You might recognise yourself in some of these patterns:

Your sleep becomes fragile — you toss, turn, wake up early, or fall asleep only to be jolted awake by racing thoughts.

Your muscles feel tight or achy, especially in the jaw, neck, shoulders, or back, and tension headaches become more frequent.

Your digestion is unsettled: frequent indigestion, stomachaches, constipation, diarrhea, or symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome.

Your ability to focus fades; you reread the same sentence, lose track of what you were doing, or feel mentally scattered.

Individually, each of these might be easy to dismiss. Together, they are often your body whispering, “This is too much.”

What would feel a little kinder to your nervous system today: one less obligation, five quieter minutes before bed, or a small, grounding ritual in the morning?

When Everyday Worry Starts to Hurt

Occasional worry is part of being human. But when worry becomes a habit, it can ripple out into serious health concerns.

Heart health: Ongoing stress can raise blood pressure, increase heart rate, and influence cholesterol levels, which over time can contribute to heart disease.

Blood sugar and weight: Chronic worry can nudge blood sugar upwards, especially in people already living with Type II diabetes, and may also feed patterns like emotional eating, which can lead to weight gain.

Hormonal and immune balance: Staying in a worried state keeps stress hormones elevated, which can interfere with immune function and contribute to fatigue and low mood.

Mood and aging: People who worry excessively are more likely to experience depression, and long-term stress can even influence cellular aging, making your body feel older than it is.

None of this is shared to alarm you. It is shared so you can see your worry not as a personality flaw, but as a genuine health factor — and one you’re allowed to take seriously.

Seeing Worry as an Invitation, not a Sentence

Worry, by itself, doesn’t fix anything. It doesn’t pay bills, mend relationships, or change test results. What it can do is alert you: “Something here matters.” From that perspective, worry becomes an invitation — not to dwell, but to tend.

You don’t have to “eradicate worry” to care for yourself. You can begin more gently:

Noticing when your body is tightening or your thoughts are spiraling.

Pausing to ask, “Is there a small action I can take here?”

Letting yourself rest when your system is clearly overloaded.

Think of worry as a knock at the door, not a storm you have to stand in forever. You are allowed to step inside, dry off, and decide, with care, what truly needs your attention next.

Journaling Prompts

When you notice worry showing up in your body (tight chest, unsettled stomach, restless sleep), what is it usually trying to draw your attention to beneath the surface?

In what ways have you learned to see your worry as a personal flaw, and what shifts if you instead regard it as a protective signal from your nervous system?

Think of a recent situation where worry stayed with you for days: what small, compassionate action could you have taken sooner to tend to what mattered, rather than staying in the spiral?

If worry is a “knock at the door” in your life, what boundaries, supports, or daily rituals would help you step inside and dry off instead of standing in the storm?

Imagine a version of you who relates to worry with more kindness and curiosity than judgment: how do they move through their day, care for their body, and speak to themselves when they feel anxious?

See Part 2 of the ‘Worry’ articles next week!